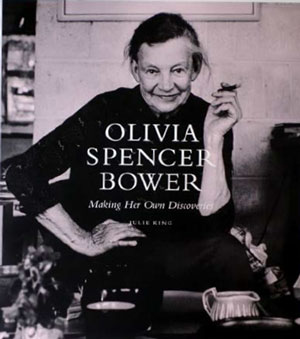

"Olivia Spencer-Bower: Making Her Own Discoveries" by Julie King

Book review by JOHN TOFT

‘I paint for myself. That’s the only way. For when you paint to please it’s not the honest thing and inhibits the chances of discovery, because there’s no point in writing or painting unless you make your own discoveries.’

‘I paint for myself. That’s the only way. For when you paint to please it’s not the honest thing and inhibits the chances of discovery, because there’s no point in writing or painting unless you make your own discoveries.’

Art historian Julie King, author of books on Margaret Stoddart and Sydney Lough Thompson, has turned her attention to the life and works of well-known Canterbury watercolour artist Olivia Spencer Bower (1905-1982).

Olivia Spencer Bower was born in England. Her mother, Rosa Spencer Bower, was a talented watercolourist. When Olivia’s elocution teacher suggested that she could perhaps go on the stage, her mother replied ‘No. She’s to be an artist.’

In 1920 the family moved to New Zealand where Olivia attended the Canterbury College School of Art. The tuition emphasised close observation and truth to nature. Olivia won major prizes, but later confessed she had been a bit of a rebel. Her fellow students included Rita Angus, Rhona Haszard, Russell Clark, Rata Lovell-Smith and Evelyn Page.

Olivia travelled to Europe in 1929 to attend the Slade School of Art. Here the focus was on drawing from the life model. Olivia announced she was sick of drawing and she also enrolled at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art where the emphasis was on encouraging students to express their own ideas.

In 1931, she returned to Christchurch, where her watercolours, exhibited at the Canterbury Society of Arts, soon attracted favourable critical comment. She also exhibited with The Group, an association of progressive artists whose members included Christopher Perkins, R N Field, Rita Angus, Louise Henderson, Rata Lovell-Smith, Ngaio Marsh and Toss Woollaston.

Olivia next spent more than 5 years in Auckland, studying at the Elam School of Art. She concentrated on portraits and figurative works, many of them painted in oils. During this period she suffered severe and recurrent bouts of ill health, which led to her spending two months in Rawene, on the Hokianga Harbour, with legendary backblocks doctor G M Smith and his wife.

In 1949 Olivia returned to Christchurch to look after her aging mother, who died in 1960. Freed from the responsibility of caring for her mother, Olivia set off for Europe in 1963. She returned two and a half years later. It was after this trip, she later declared, that she at last considered herself to be a New

Zealander. She lived and worked in Christchurch for the rest of her life.

Shortly before her death from lung cancer in 1982, Olivia established a charitable trust,

The Olivia Spencer Bower Foundation, to fund an annual award for promising and emerging artists and sculptors. It was open to both males and females but she wanted to favour female artists because she felt they had not received the recognition they deserved during her lifetime. A recipient wrote, ‘The award is unusual in its focus on simply supporting the artist, with no output requirements. Because of this I can tell it was set up by a fellow artist who understood the artistic process. I feel free to do whatever I need to do to nourish my work...’

John Coley, former Director of the Robert McDougall Art Gallery wrote ‘Olivia was a leading member of The Group, which annually presented exhibitions of works by the country’s more advanced original artists. She was undoubtedly among the small group of exceptional watercolourists produced in New Zealand.’ Olivia’s paintings are in many of New Zealand’s main public galleries.

In 1968, the Robert McDougall Gallery organised a retrospective exhibition of her work which toured the country. She won first prize in the watercolour section of the National Bank Art Awards for her landscape Open Country in 1971.

Olivia is probably best known for her landscapes. Her favourite locations were the Waimakariri River, the Mackenzie Country, Kaikoura and Punakaiki. She also produced a number of memorable paintings of the verandah at the family farm near Swannanoa. Her early watercolour style is characterised by accurate drawing over which the painting was built up with carefully laid, thin transparent washes. Later, she also painted in a looser, more Modernist style, exemplified by her painting Mackenzie Basin. Interestingly, she continued to alternate between the two different styles from the 1940s until the end of her career. Her mother, who had no time for Modernism, had one of Olivia’s early works above her mantelpiece. If a visitor admired it she would say ‘Yes, Olivia used to paint well. What a pity she doesn’t do that now.’

Julie King writes in her introduction that her aim was to present an introduction to Olivia through a selection of watercolours, paintings, drawings, prints and illustrations that represent the multiplicity of her interests. Olivia Spencer Bower: Making Her Own Discoveries is a very readable and informative account of the artist’s life and works.