by Roderick J. Weston

Cultural appropriation is the unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the customs, practices, ideas, and other cultural elements of one people or society by members of another and typically more dominant people or society, often for personal or financial gain.

o.nz/ Sian Montgomery-Neutze. )) This topic has come to the fore over recent years and while the subject relates to all ethnic groups globally, this discussion will be confined to the use of Maori culture in New Zealand art.

In the 19th century, early New Zealand artists recorded in oil and watercolour, aspects of life in the new British colony, particularly the landscape but also the way of life of the native Maori people. Of particular interest to such renowned artists as Goldie and Lindauer, were the tattooed faces of Maori leaders, both men and women. Their aim was to record this aspect of Maori culture, which was a novelty to the colonists, at a time when photography was in its infancy. At that time, the artists would presumably have executed their portrait and other paintings with the approval of the subjects. Today a different attitude has developed. Writers, particularly journalists ride the wagon of the freedom of speech and what would have been banned in the nineteenth century is acceptable today. The writers freedom of speech has been transferred to art, such that artists feel they can paint and depict what they want to and to make money from their activities. Therein has arisen a problem.

Today, intellectual property (IP) has become big business which is illustrated by the financial fortunes earned from the creation of lyrics and popular music and such inventions as the compact disc and computer-operating systems. Maori feel that their culture belongs to them and should be protected by todays IP laws. For an interesting discussion on Maori IP, see

Sharing the taonga: who owns Maori intellectual property? by John McCrone, April 8, 2016

The geometric and other artistic designs which are associated with Maori life and seen most notably in wharenui and Ta moko, are taonga (treasure) to Maori and the purposes and applications of this art are sacred. Ta moko in particular contains ancestral tribal messages specific to the wearer. These messages tell the story of the wearers genealogy, social standing and tribal affiliations. Therefore, the moko is much more than an art form, it is an historical record and the moko designs are considered to be intellectual property. The use of these designs by Pakeha for capital gain is currently causing much angst among Maori, who believe that such appropriation by non-Maori should be disallowed. The Wai-262 claim (1991) to the Waitangi Tribunal and the Mataatua Declaration (1993) are attempts to protect Maori culture and their intellectual property, but the conversion of such claims to law is very slow. These issues are described in

the Library of Congress report "New Zealand: Mori Culture and Intellectual Property Law"

Geometric designs used for body art today are referred to by two different terms, Kirituhi and Ta Moko. Kirituhi is a modern practice (1999 - 2000) of tattooing arms and body, available to anyone and in the past 10 years has become widespread. The tattoo is created with needles and the skin surface is left smooth. International celebrities who have such tattoos include actress Angelina Jolie, boxer Mike Tyson and entertainer Robbie Williams. Ta moko involves traditional Maori geometric designs which signify the wearers genealogy, iwi affiliations and status. Ta moko is sacred to Maori and is carved into the skin of the face and head, using chisels made of bone or stone by a Tohunga ta moko, the process leaving the skin with grooves filled with natural pigment.

Some recent examples of the appropriation of Maori art, especially Ta moko and considered offensive to Maori people are discussed below.The first example occurred recently when Australian fashion

model, Gemma Ward appeared in a photo shoot for the Australian edition of Marie Claire magazine, wearing a moko painted on her chin. Ngarino Ellis, a senior art history lecturer at the University of Auckland said the use of the traditional facial marking on a non-Maori model was offensive. He said it was insensitive to simply paint a generic design on a person with no connection to the culture. Marie Claire later published an apology saying, We apologise unreservedly if we have caused offence, said associate-editor

Anna Saunders Daily Mail

.

The second example of misappropriated work is that of Whangarei artist Victor Te Paa, whose art was incorporated on merchandise shown here, sold by 1stnewzealand.com a Vietnamese company, without any reference to, permission from or benefit to the artist. Noted barrister and cultural IP rights expert, Maui Solomon, who assisted with the Wai-262 claim in 1991, said the work of Maori artists is a manifestation of whakapapa and tupuna so when the work is used without permission, it not only causes personal offense, but cultural and moral offense. It is deeply rooted within the rich mosaic of Maori identity and ancestry and so theres a direct relationship between the person, their art and their ancestors. Thats often the difference between Maori art and other artworks.

A further example of Maori grievance over misuse of their art occurred when Nelson artist Nikki Romney created a painting Taking Tikanga to the World, which shows a globally diverse group of young non-Maori women wearing non-traditional moko against the backdrop of a famous portrait by Charles Goldie. Romney was criticized heavily on social media for the disrespectful work and received serious threats to her business. Romney said art is not meant to be stifled and if we live in a society where art is shut down or restricted, then I believe we have lost who we are a diverse group of people from different cultures, generations, beliefs and values. Anyone, no matter their religion, cultural or political belief, must be free to express themselves.

This is an example of the new attitude referred to above.

Yet another example of cultural appropriation in NZ art was the painting of TVone newsreader Oriini Kaipara, by Auckland artist Samantha Payne, which clearly depicts her moko kauae, but the painting was created without the knowledge or consent of Ms Kaipara.

The painting was later withdrawn from sale. Ms Kaipara commented Im not against artists, journos and whomever else using my image to promote our ao Maori and Maoritanga but selling MY moko for profit and for YOUR self-gain is damn disrespectful to say the very least. (www.tvnz.co.nz/one-news/ Sunday May 10, 2020).

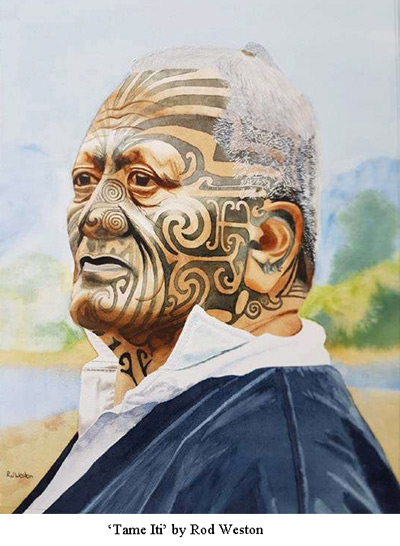

The most well-known New Zealander who wears an extensive and detailed moko is Tuhoe kaumatua Tame Iti. While many dozens of photographs of him can be seen on various websites such as Pinterest, very few portraits of him have been painted. One of these is the (2012) oil painting by Auckland artist, Sofia Minson, which is shown here (above) and was modelled on a photo taken by Jos Wheeler.

This year, I also completed a portrait of Mr Iti, shown here, which clearly depicts his moko. The painting will be gifted to Mr Iti. The artistic beauty and the superb geometry of the moko attracted me to paint this portrait, in addition to the challenge of doing it in watercolour. Furthermore, I considered his pose was especially suitable for a portrait. All these features were originally captured by Birgit Krippner, whose photograph of Mr Iti, along with an article about him by journalist Ann Warnock, were published in NZ Life and Leisure magazine (issue 90, 2020). I therefore sought permission from the subject, Mr Iti, the photographer, and the magazine editor before using their material to create the portrait.

Other people might also be involved in the creation of reference material, such as the artist who designed the moko and the artist who carved the moko onto Mr Itis face. These artists are part of a team involved in the copyright of what is seen in the portrait. I am not Maori and have no connection to Maori culture apart from an admiration for their art and the skill of their artists and so it is especially important that artists like me, seek permission from the subject as well as all others who might hold copyright for the image being used to create a (portrait) painting. These conditions are requirements of entry, among others, to the Adam Portraiture competition that is run by the National Portrait Gallery in Wellington.

Portraits are not seen frequently at watercolour exhibitions and those of Maori even less so.

However, the message to take from this article is that artists can create a portrait only after gaining permission to do so from the subject and also from any person who created material used as a reference for the painting, including photographers, magazine editors and journalists. If the painting is to be exhibited and ultimately sold, then the artist must seek clearance from the copyright holder.