by Martin Necas

Such a harsh and categorical statement published in an arts society newsletter? Pure blasphemy! I think I have some explaining to do before I get pummelled with disused paints, speared with old brushes and dismissed dishonourably from society. Eeek! Maybe I should have kept this piece anonymous after all.

So, before you judge me, please hear me out. Its just that I have never met anyone who has credited their success to talent. Have you? Surely if talent was a real thing, then people would acknowledge they have it, similar to acknowledging a fine moustache or big feet. But everyone denies it.

Lets suppose for a moment that talent really existed. Imagine how some everyday conversations would go:

You in a caf: Thanks, thats a heavenly coffee. I sure needed that!

Barista: Oh dont mention it, I just make it up as I go. You know, talent.

Or,

Congratulations on publishing your PhD thesis, what an awesome achievement!

Newly decorated Doctor of Philosophy: Its nothing, really. Somehow, I was born with a unique ability to relate quantum mechanics to material nanoscience. Just talent. Discovered it when I was three. Im also multilingual and play competitive squash. But, its all just so easy. I feel like a fraud compared to other people. Its all

due to my talent.

Ridiculous, right? You get my point. Yes, yes, I know some people will learn certain things faster than

others. Some peoples physical and mental characteristics make them particularly suitable to excel in a particular endeavour.

Some people are statistically better drivers than others (women seem to be far better than men) and some people will become competitive athletes and others wont. I, for one, stand no chance of ever becoming a yoga instructor. Utterly inflexible. But my point is that the path to success in any walk of life is not due to

some illusive and mysterious thing called talent. Instead, success is largely due to a combination of quality training, repetition, perseverance and an analytical approach (call it science). Or as the saying goes: practice makes perfect.

Learning to master art is no different. For an individual artist, the steps towards success are incremental and they are also incremental for art as a whole. One artist learns from another. We copy, imitate and grow; eventually developing our own style. Art as a human endeavour also evolved in steps from sketching on cave walls with coals and ochre to the myriad of modern techniques and media.

And this brings me to the importance of critical analysis and scientific elements in art. If talent was a real phenomenon, dont you find it astonishing that 40,000 years of art history has failed to produce a single prodigy with the natural talent for such basic an idea as a single-point linear perspective?

Just picture the monumental achievements of antiquity from the pyramids to the Acropolis. None of it was ever planned or sketched using perspective, the way our own eyes see it; a 3D object on a 2-dimensional plane. The discovery of perspective is credited to Filippo Brunelleschi in the 1400s. But discovery is perhaps the wrong term. Brunelleschi did not simply come across perspective by some stroke of luck as the term discovery implies. He did not have some superb talent that naturally guided him toward perspective. He was a trained architect, engineer, mathematician and designer. He applied rigorous scientific methods (observation, analysis, experimentation) to uncovering the principles of perspective drawing. He collaborated with others (scholars, craftsmen and artists), wrote treaties on the subject, studied, lost sleep over it and eventually produced the first truly 3D wire-mesh diagrams and full drawings, the way you would do it today using 3D software.

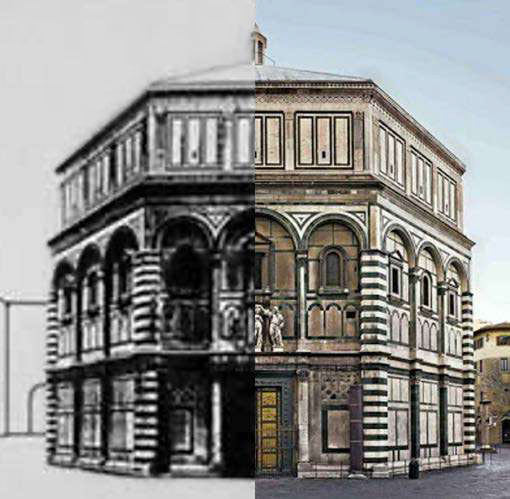

The first such image is of the Baptistry in Florence. It is astonishing in its likeness to the standing building.

So, next time someone looks at your artwork and says to you: wow, you are talented, I could not do that!, correct them: Not at all. Its all training, repetition, perseverance and science. Sadly, they probably wont believe you. The belief in mysterious invisible forces is simply more alluring that the belief in plain old hard

work!

Figure 1:

A single-point perspective drawing of the Baptistry in Florence superimposed on a photograph of the real building.

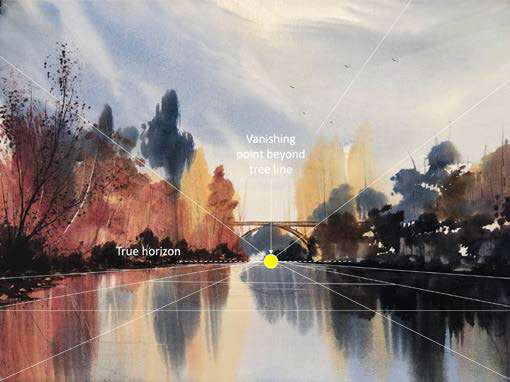

Figure 2:

Figure 2:

A fast-and-loose landscape watercolour painting of the Narrows Bridge in Hamilton (author) with application of linear perspective shown.

References:

References:

1. Edgerton, S. (1973). Brunelleschis First Perspective Picture. Arte

Lombarda, 18(38/39), 172-195. Retrieved October 14, 2020, from

JSTOR.org

2. Trachtenberg, M. (2014). To Build Proportions in Time, or Tie Knots in Space? A Reassessment of the Renaissance Turn in Architectural Proportions. Architectural Histories, 2(1), p.Art. 13.

3. Harris, B. & Zucker, S. (2012). Linear Perspective: Brunelleschis Experiment. Khan Academy