by Martin Necas

One of the most beautiful aspects of watercolour is its natural tendency to flow and blend. Watercolour artists sometimes say that the best results are achieved when "watercolour is allowed to paint itself". But this special property of watercolour can be elusive and hard to achieve. When I began my watercolour journey, I did what many students of watercolour initially want to do, and that is to restrain the watercolour to some manageable sections and then try to combine these sections into a cohesive painting. I sometimes describe this style of painting as "colouring by watercolour". One can achieve good results this way, but the process is tedious and difficult to get right. It relies on the artist mixing the colours perfectly and blending one section into another seamlessly. This style of painting is a minefield with dangers around every corner. Non-experts often produce disappointing results where different sections of the painting appear as disconnected cardboard cut-outs. The work is often illustrative in nature. It lacks authenticity.

The first watercolour book I ever I bought was written by a well-known English artist Dave Woolass and titled

"Ready to Paint in 30 minutes: Landscapes in Watercolour"

. Dave comes from a traditional English style of watercolour characterised by abundant small detail often done with a round brush.

I studied his book eagerly and competed many of the exercises. It was a great experience for a budding watercolourist, but at the end I was left a little disappointed. It took 30 minutes to prepare a sketch using transparencies provided in the front of the book. Then it was a simple matter of painstakingly colouring in the sketch. The process felt rigid. There was little joy, spontaneity or creativity in the process. Because some sections were done in defined layers (washes or glazes), there were too many hard edges even around objects that should be soft and diffuse.

I realized this was not the style that suited me. I discovered that I was more interested in a faster and more expressive style of painting in the tradition of Edward Seago, Edward Wesson, Ron Ranson or as showcased by current Australian masters represented by Herman Pekel, Alvaro Castagnet and Joseph Zbukvic to name a few.

Instead of the preparation taking 30 minutes, I wanted to be more or less finished by then. And instead of using multiple washes and meticulously mixing colours, I wanted my paintings done in only 1-2 washes and with colours mixed on the fly on the palette, or in the brush or directly on the paper.

The secret to achieving a good result using a fast watercolour approach is to paint quickly, decisively and to apply thick and rich colour into a damp background where it will blend into the surroundings. If the colour is too thin and watery, it will diffuse and combine with other colours in the wash turning into mud. Mud is probably the most offensive word in watercolour vocabulary. Rightly so. As I like to point out to students of watercolour: even mud is not mud coloured. The control of water content is absolutely critical in avoiding mud, but it's not too difficult to learn. The most common mistake is simply using too much water and too little paint.

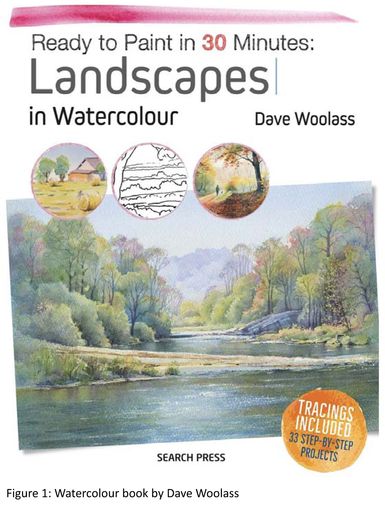

In the example below, we will look at the process of painting a river scene, the Kawerau River. The painting is 24 x 18 inches (609 x 457mm, about imperial sheet) in size on Fabriano Artistico 100% cotton paper, using regular Winsor & Newton Cotman colours: Lemon Yellow, Raw Sienna, Ultramarine, Burnt Umber, Light Red, Payne's Gray and Alizarin Crimson. The brushes used were a 4.5cm natural hair flat brush, a 1.5cm mixed hair flat brush and a size 3 rigger brush, however, a comparable result could be achieved with a large natural hair mop or even with a mixed hair round. The tools don't matter too much.

First, the sky and water were painted wet-into-wet using only about 25 broad, sweeping brush-strokes. Before the first wash was fully dry, the background and middle-ground were added using progressively thicker paint with warmer tones. As the underlying paint started to dry, more details were dropped in using simple vertical brush strokes (Figure 2). Varying the tone and hue is important at this stage to create variation and avoid monotony. Next, the water section was dampened, and a few reflections dropped in using vertical brush strokes. These do not need to be a precise copy of what's above the water. A rough approximation will do.

Once dry, the distant shore and central island were added. A few rocks were scraped out with a corner of a plastic card and a few darker rocks were added using the corner of a flat brush. The foreground details including the scrub on the left and overhanging tree were painted last (Figure 3). Most of this section is dry brushed. A rigger was used for branches and twigs.

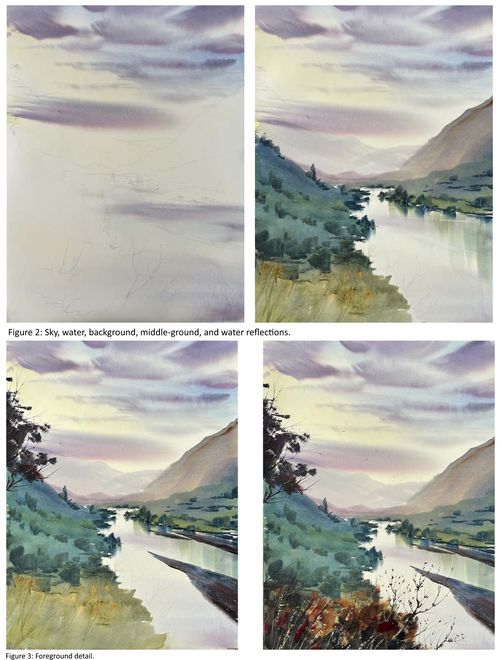

Setting the painting behind a mat (or untaping the edges) allows for better assessment of the tones and hues.

Another trick to judging of tones is to take a photograph of the painting and convert it to black and white (Figure 4). A total painting time from sketch to finished painting was 70 minutes.

Fast and loose approach to watercolour painting can produce beautiful results, with flowing colours, soft blends, smooth gradients and spontaneous natural brushstrokes that become an integral part of the painting. If you are new to watercolour or you haven't tried this approach for a while, consider it for your next project. Simply open up your favourite painting kit, set your timer and go for it with a stubborn determination to do it all in one hit. You may be pleasantly surprised at what you can achieve.