by Martin Necas

For experienced watercolour artists, trees in a landscape usually dont present much of a challenge. Experts have had plenty of opportunity to develop their own style and to settle on a few techniques that they like and that fit their compositions and artistic aspirations. For students and junior artists, however, trees often present an omnipresent and formidable challenge. Not only are there too many types of trees, but trees may appear very different depending on distance, vantage point, focal point, time of year and light conditions. How can one account for this bewildering variety of natural forms? The best thing is not to worry about the detail, simplify the scene and paint it quickly using few authoritative brush strokes.

In this article, we will explore one of my favorite solutions for painting trees by using a hake brush, flat brush and a rigger. The use of the hake brush was popularized by a British watercolour artist Ron Ranson (1925-2016). Many artists have followed similar techniques using a variety of other brushes to achieve a similar effect. The advantage of the hake brush is its enormous water retention and ruthless efficiency, but similar results can easily be achieved using a large round brush, large squirrel mop or even a synthetic fan. The tool matters less than the technique.

One style of painting trees that I am not very fond of can be described as stabbing at the paper with a small round brush and trying to shape each bit of foliage. The process can be tedious and often yields forms that are unconvincing, unnatural, rounded and somewhat illustrative in style. So, before we have a look at the fast-and-loose technique, I should make an important disclosure. We are not going to be doing much purposeful painting as such. Instead, we are going to use a minimalist approach to suggest tree forms using brush strokes, colours and tones in a way thats impressionistic but sufficiently realistic to convince the viewer. Sometimes, all thats required is a single touch of the brush.

Using the brushes

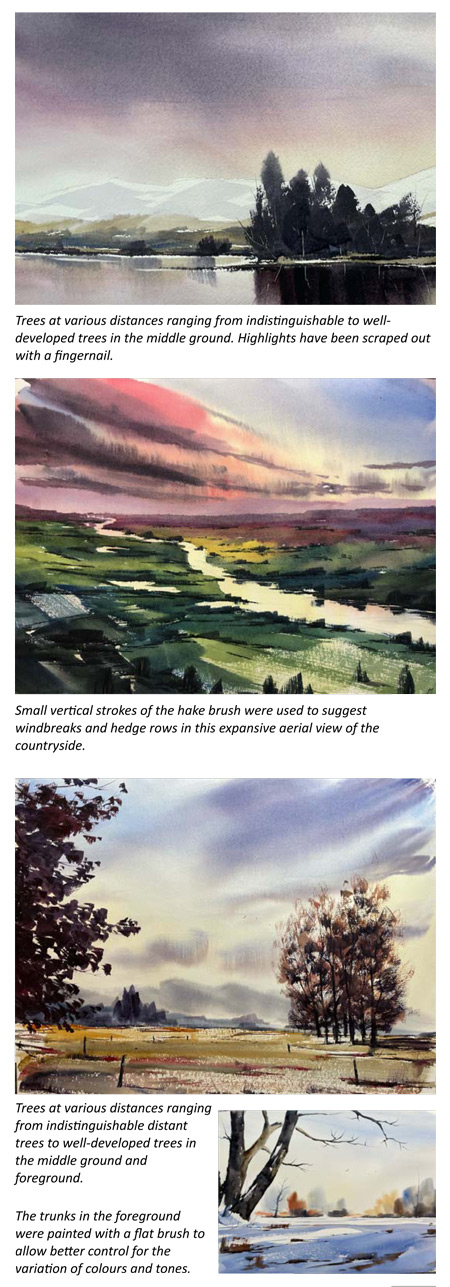

At first sight, the hake brush may appear as a large and cumbersome tool, but in reality, it is an incredibly versatile and delicate instrument. When loaded well, the edge of the brush is razor-sharp allowing you to paint straight lines such as tree trunks and major branches. The corner of the brush can be used to make triangular vertical strokes for distant trees or loose foliage. A semi-dry brush will bend and maintain its shape allowing you to stamp, drag or feather in large sections of foliage quickly and efficiently. And a dry brush used very lightly from a variety of angles can produce the impression of fine twigs on skeleton trees as well as ground cover. The flat brush can be used for more delicate shaping of tree trunks and major branches and the rigger is best for painting finer branches that have a convincing natural character. To achieve a tapering branch, press a loaded rigger down and drag out the branch using jerky movements reminiscent of a trout swimming up a stream followed by a quick flick at the end. A plastic card, palette knife or fingernail can be used to scrape out some highlights in darker areas to create contrast but do this sparingly. The most important aspect of fast and loose painting is that it is precisely that: fast and loose. Its spontaneous, impressionistic, and not constrained. There is an element of randomness. The spontaneity of the brush strokes adds to the beauty, quality and visual consistency of the painting. Most fast-and-loose paintings can be completed in half an hour, and many can be done in a single session without drying and re-glazing. As with all watercolour techniques, judging the water content can be tricky and requires practice.

Trees in the distance

Distant trees usually appear to us as a uniform mass of desaturated colour due to atmospheric perspective. Fine details are indistinguishable, but there is usually some gradual variation of colours or tones. On the edges of a mass of trees, you may be able to observe the odd branch or tree trunk. Distant trees lend themselves well to wet-into-wet technique.

Oftentimes, there may be several layers of trees in the distance. This can be represented by color and tonal variation. Lighter, cooler and desaturated in the distance versus darker, warmer and richer closer. Most of the time you can get away with painting more than one layer of distant trees all at once without drying in-between simply by using less water and more pigment as you move forward.

Depending on light conditions, distant tree rows, windbreaks or hedges can silhouette sharply against the background. Such features can be added with a single vertical stroke of the hake brush.

Trees at the focal point

Trees in focus in the middle-ground or foreground need to be well developed with more detail and heavier textures. At a closer distance, gaps between the foliage will become visible and these need to be preserved. Shadows become more important. Its really just a matter of observation and approximating the tonal values. Its usually sufficient to have two tonal values in a tree, applied one after another and letting them diffuse. The process should still be fast and spontaneous to fit with the character of the rest of the painting.

Trees in the foreground

Trees in the foreground are usually represented only by trunks with a few branches. Since the foreground is almost never the focal point of the painting, its important that any trees in the foreground dont draw the viewers attention from the focal point and do not restrict the field of view. Less is usually more. A carefully placed tree with a couple branches may help frame the centre of interest nicely.

Trees reflecting in water

Water is a beautiful element of a natural landscape. Its surprisingly easy to paint simple reflections in water by wetting the paper and dropping the reflections in by using quick vertical brush strokes in the downward direction. Any details (such as trunks and branches) can be loosely indicted as well. Since the paper is already wet, the paint needs to be applied thick, otherwise it will dilute and become insipid. Remember to account for everything reflecting in water including the sky, trees, grasses and the waters edge or bank. The vertical dimension of a reflection should usually be similar to the true object, but otherwise reflections dont need to be precise copies of whats above the water to look convincing. They can simply be rough approximations of the colours and tones above the water. Its best to paint reflections quickly and let them be. Overworking reflections can easily turn luminous water into mud.

Shadows

Shadows can make or break a painting. Shadows add volume and realism. They indicate the source of light, and they also help indicate the topographical contours of the landscape. Without shadows, the painting can look flat and featureless.

Putting it all together

The fast-and-loose technique is a great way of painting trees as well as other elements of the landscape including skies, distant landforms, rivers, rocks and other natural features. The technique can be adapted to other subjects from urban landscapes and still life. So, what are the most important aspects of fast and loose painting when it comes to trees? Do it once, do it with confidence, leave it alone, dont over-work it and resist the urge to tinker with it. But most importantly, enjoy every brush stroke and make them count.

References:

Ranson R. Watercolour Painting: The Ron Ranson Technique. Blanford Press, 1986.

Ranson R. Watercolour Fast and Loose. David & Charles, 1986.

Ranson R. Distilling the Scene. David & Charles, 1995